1917 – When the advertising world came to St. Louis (Part 2)

Patriotism and Parades – Part I: Cue the speeches

The specter of World War I loomed large over Associated Advertising Clubs of the World conventions by 1917. While many businesses curtailed activities due to battles being waged overseas, stateside advertising men and women prepared to lend their communication expertise in earnest to the nation. Events in Europe since 1914 and heightened by America’s recent involvement in the war influenced the tone of the meetings and mood of the participants. In the Associated Advertising May 1917 magazine, Lewellyn Pratt, Chairman of the National Program Committee reaffirmed the club’s resolve, “Tell the clubs we have been asked whether the War will have any effect on the convention. I answer, Yes. It will have the effect of making the St. Louis Convention the greatest meeting in our history. Men will gather by the thousands in St. Louis in June to see how American thought and enterprise can best be mobilized to make the world safe for democracy and business.”

As they had done earlier in Philadelphia, the Convention Board of the Advertising Club of St. Louis used posters to advertise the convention and raise the patriotic spirit. Said one poster, “All businessmen are invited to attend this important annual conference of the country’s most capable advertisers, that by such association they may better their commercial methods, partake of the hospitality of St. Louis, and, most important of all, ‘do their bit’ in meeting the exigencies of our greatest National emergency.” Another poster helped justify those who may have felt it their obligation to stay away from the European front, “Your country needs you! If not your brawn – then your brain.” The poster continues by describing the St. Louis convention as “the most important commercial conference of the year – especially significant at this time in view of the problems brought upon us by the war. St. Louis offers an opportunity for the Captains of American Industry to concert their energies for the common good of the country. The Nation needs all its brain as well as brawn. Come to St. Louis in June.”

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported that the 13th annual convention would be a “patriotic business convention” and called it a “Calling of Commerce to the Colors” (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Meeting of Ad Men Will Be Patriotic, May 6, 1917, pg. 4B). The New York Times in their June 6th issue shared stories from the convention of how advertising aided the English and Canadian war efforts on raising volunteers and donations and quoted St. Louisan convention speaker, George W. Simmons of Simmons Hardware, on patriotism, “Those of us who stay behind can help win the war just as those who go to the front. There is just one way. We must follow our leaders as surely and as faithfully as our brothers who respond to the military commands of their officers” (New York Times, How Advertising Has Helped in War, June 6, 1917, pg. 7). Even President Woodrow Wilson recognized the club’s spirit, “May I not congratulate the Associated Advertising Clubs upon their purpose to assist in mobilizing the best thought and promoting greater efficiency in all lines of business in these times of stress and exigency? It would be of the greatest benefit if the convention could be employed to steady business and clear the air of doubts and misgivings in order to make for greater unity of purpose in winning the great war for democracy and civilization.” (Associated Advertising, June 1917, pg. 14)

Patriotism and Parades – Part II: Cue the bands

While patriotic speeches and presentations were daytime activities, the evening of June 4th belonged to a St. Louis style first-class patriotic parade.

The Associated Advertising May 1917 magazine provided background on what the parade committee of the Advertising Club of St. Louis expected and planned.

“Every float in the advertising parade must be illuminated, must cost at least $250, and must tell a story. These and other rules which have been adopted by the parade committee of the Advertising Clubs of St. Louis are for the purpose of making the parade fully live up to the reputation of St. Louis in such matters.” The article continues in describing the level of expert help available, “In St. Louis, which has been famous for its pageantry for a generation or more, there are numerous professional float builders, with workmen, tools, forms, and other facilities for making anything imaginable in the way of a float.”

“The committee provides horses with men to lead them, the means for lighting the float, costumes for such human figures as are called for, and the people to wear the costumes.”

Once again, St. Louis and other businesses supported the Ad Club’s efforts. To keep the floats lit, the Prest-O-Lite Company of Indianapolis supplied acetylene gas and batteries, while St. Louis’ United Railways Company provided the overhead current of trolley poles. United Railways even supplied each float with a local streetcar conductor to march alongside to keep the trolley on the wire!

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch reported on the parade’s success the next day on June 5th and called it “perhaps the most successful pageant of its kind ever held in St. Louis. It was successful artistically, commercially, and as a stimulus to patriotism.” The paper further acknowledged Mayor Kiel’s attendance in the reviewing stand, cheers for the mayor, marching bands playing patriotic music, sailors from the U.S.S. Kirtman, militiamen from the First Missouri Regiment, and advertising clubs from around the country.

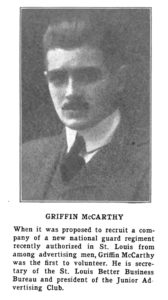

The Advertising Club of St. Louis was in full force and led the parade marchers with “Saint Louis” riding ahead on a white horse. The Ad Clubbers carried banners saying, “Last year we offered the glad hand. This year we give it.” According to the Post article, the Junior Advertising Club of St. Louis marched next and “the youthful members of the club exhibited far more ‘pep’ than their older associates, making a great deal more noise and joking more with the spectators.” [Editor: Some things never change. To learn more about AD2 click here]

Each state delegation then marched, and each club was noted in the Post-Dispatch article. Among the highlights “The Kansas City delegation showed an advertising preference for a reference to their city as ‘K.C.’; the Chicago contingent were possessed of fine voices, which they used liberally in singing all along the parade route; the Joplin delegation dragged a mining car the entire length of the march, but seemed to enjoy the labor; the New York delegation included several women delegates marching at the head of the group; while the San Francisco club took things easy traversing the parade route in automobiles.”

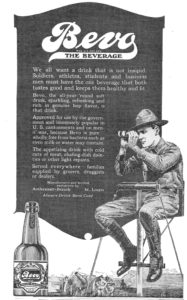

As the final marchers made their way to the grandstands, floats were next. In addition to the Ad Club’s float, many St. Louis businesses participated. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch float represented its new headquarters being built at 12th and Olive Streets, while the St. Louis Globe-Democrat float had to be abandoned when the front axle of the wagon carrying it broke at Jefferson and Olive Streets leaving its four newsboys stranded. The Lemp Brewing Company included Falstaff on their float and Bevo was advertised by five pony teams hitched to a small wagon. Union Electric Company represented a “matchless kitchen” complete with modern electrical cooking and heating devices; Simmons Hardware Company showed Keen Kutter tools being made on its float, and Washington University’s float highlighted its various courses offered at the school.

William C. D’Arcy and the new presidency

Even with all the pomp and circumstance, the men and women of the convention were in St. Louis for business. “Flags were everywhere. Patriotic music stimulated the senses from every possible occasion. Yet there was no visible excitement. The feeling that ran through the convention was too deep, too earnest. It was feeling that hungered for action.” (Associated Advertising, When Nation Called Clubs Leaped to Service, July 1917).

In addition to pledging to raise over $2,000,000,000 for the Liberty Loan and $100,000,000 for the Red Cross in national advertisements, participants heard speeches from leaders of industry, voted on important topics, and worked to educate the public on the theme that “Advertising Lowers Cost of Distribution.” “Speakers in the convention will produce facts and figures to prove that advertising by increasing demand, multiplies production, and does not increase, but actually lessens the selling price. A demonstration of this proposition will also be offered in the advertising exhibit, which is to be open to the public in the City Hall rotunda.” (St. Louis Post-Dispatch, Advertising Men to Talk Business in Meeting Here, May 20, 1917 pg. 2B)

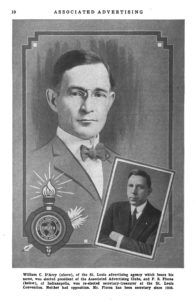

One of the final orders of business was to elect a new AAC of W president. Running unopposed, peers described William Cheever D’Arcy as “modest, capable, direct in his methods, and an unusual organizer.”

“Summing up the character and accomplishments of William C. D’Arcy in placing him in nomination before the St. Louis Convention, Lafayette Young, Jr. of Des Moines, retiring vice-president of the association, said ‘the fact he (D’Arcy) had in eleven years built an advertising agency from almost nothing to a business of more than $2,000,000 was enough indication of his ability as an organizer.’ Festus J. Wade, of St. Louis, said during the past week, that the ‘people of St. Louis consider Mr. D’Arcy one of their most useful citizens. Mr. D’Arcy is not known particularly as an orator or as an evangelist, but he is known as a builder, a creator, and an organizer. He assembles. He has some of those stern military qualities which I believe most of you will admit are most appropriate at this time in building this organization into a better fighting force. Mr. D’Arcy, as you know, is cool-headed and sound judgment, able and a man of highest personal and business character. He hits the line hard but plays the game absolutely square in every respect.’” (Associated Advertising, July 1917).

“In his own business, in the Advertising Club of St. Louis, in the agency division, and in his work for the Associated Advertising Clubs, he has given ample evidence of his ability as an executive and an organizer. He knows how to choose helpers, how to establish points of common contact that will hold them together, and how to obtain the best that is in them. His hand is firm. His mind is keen. He is quick to recognize peculiar ability in others and has admirable facility for weighing and adopting suggestions.” (Associated Advertising, July 1917).

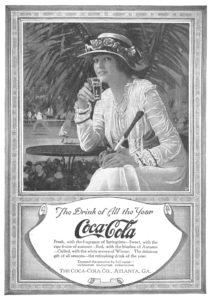

D’Arcy, whose advertising agency brought nationwide prominence to Coca-Cola since its involvement in 1906 and began servicing the Anheuser-Busch business in 1914, graciously accepted the honor by saying, “The army of the Associated Advertising Clubs, something over 16,000 strong, representing the cosmopolitan business of advertising, is a wonderful force and not duplicated. As the army’s chief officer, guided and inspired by the ruling units that you have created and conscious of the sound of your call, conscious of the picture of your faces, I reaffirm my acceptance and pledge my all to press forward and upward in this great work. My personal affairs are my pleasure, but your affairs are my duty.” (Associated Advertising, July 1917, pg. 13).

D’Arcy would be re-elected to a second term as AAC of W president in 1918 and he was a founding member of the American Association of Advertising Agencies (4As) which organized during the St. Louis convention in 1917. He later served as the 4As president in 1922 and chairman from 1933-1934. D’Arcy led D’Arcy Advertising from 1906-1945, held numerous corporate board positions and died in St. Louis at the age of 74 on July 21, 1948. He was elected to the AAF Advertising Hall of Fame in 1951 and the St. Louis Media Advertising Hall of Fame in 2007.

In our final installment, we’ll look at the important role our newly formed Woman’s Advertising Club of St. Louis played in the convention as well as how members of the Advertising Club and the Grand Opera Committee joined with civic leaders to build one of the convention’s lasting legacies, The Muny Opera in Forest Park.

- The Associated Advertising Clubs of the World published a monthly magazine that highlighted activities, personalities, and educational articles. This is the cover to the June 1917 issue of the 13th annual convention held in St. Louis, June 3 to 7. (Associated Advertising)

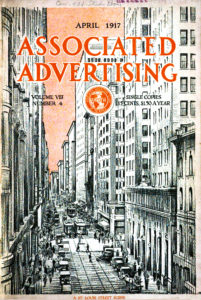

- The Associated Advertising April issue published an outline of the plans of the St. Louis Program Committee and featured this crayon cover illustration showing a St. Louis street scene of Olive Street looking west from Fourth Street. It was inspired by a photograph from James W. Booth, advertising manager for the Missouri Pacific. (Associated Advertising)

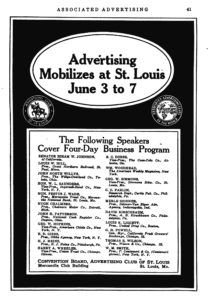

- St. Louis convention speakers featured captains of industry, finance, and politics including Senator Hiram Johnson (former governor and senator from California); H.J. Heinz, President of Heinz Company; John Patterson, President National Cash Register Company; Festus Wade, President Mercantile Trust Company; John Willys, President of Willys-Overland Company; Hugh Chalmers, President Chalmers Motor Company; and George Simmons, Vice-President Simmons Hardware Company. (Associated Advertising)

- A specially designed red, white, and blue patriotic badge given to all registered delegates of the 1917 convention. The badge combines the AAC of W “Truth” emblem with the Advertising Club of St. Louis “Forward St. Louis” emblem connected to a bronze key symbolic of the hospitality of St. Louis and signifying that the gates of the city are open to all visitors. (Associated Advertising)

- The St. Louis Globe-Democrat takes an interesting approach in extending the “glad hand” of welcome in this 1917 advertisement. The United States’ recent involvement in World War I played a large role in promotions and discussions at the convention. (Associated Advertising)

- Close up of Associated Advertising Clubs of the World “Truth” emblem letterpress block used for printing. (Ken Ohlemeyer private collection)

- Reproduced from the St. Louis Post-Dispatch article June 5, 1917 highlighting the successful AAC of W advertising parade. (St. Louis Post-Dispatch)

- From marching in the parade to marching with the national guard, President of the Junior Advertising Club of St. Louis and secretary of the St. Louis Better Business Bureau Griffin McCarthy was the first advertising man to join the regiment. His name is immortalized in the Roll of Honor plaque as one of many St. Louis advertising men to serve their country. (Associated Advertising)

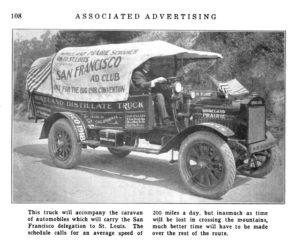

- Image of the San Francisco Ad Club “covered wagon” that made the 2500 mile west-to-east trip to St. Louis for the convention. Many San Francisco Ad Club members used their automobiles along the parade route during the marching portion of the advertising parade. (Associated Advertising)

- William C. D’Arcy was elected president of the AAC of W in 1917 and again in 1918. He was also a founding member of the American Association of Advertising Agencies organized during the convention. D’Arcy let D’Arcy Advertising to national prominence from 1906 until his retirement in 1945. He was elected to the AAF Advertising Hall of Fame in 1951 and the St. Louis Media Advertising Hall of Fame in 2007. (Associated Advertising)

- D’Arcy Advertising frequently advertised their services in the pages of Associated Advertising. Reproduced here is an ad from 1917 featuring the D’Arcy headquarters and unique logotype. (Associated Advertising)

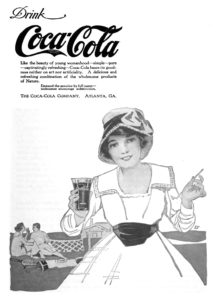

- Winning half of the Coca-Cola account propelled William C. D’Arcy to open the doors to D’Arcy Advertising in St. Louis on August 23, 1906. What started as a $3,000 account in year one, grew to $25,000 in year two and the long-standing relationship with D’Arcy and Coca-Cola was formed. D’Arcy and his team produced many iconic advertising moments from 1906 to 1956. (Associated Advertising)

- Another St. Louis produced Coca-Cola advertisement from D’Arcy Advertising featured in Associated Advertising magazine in 1917. As general circulation magazines improved in quality and four-color printing, D’Arcy and Coca-Cola used quality illustrations and wholesome models to promote the soft drink. Also, note during this period, many D’Arcy ads featured its logotype. Can you find it in the Coca-Cola ads? (Associated Advertising)

- D’Arcy Advertising began their long relationship with Anheuser-Busch in 1914 with the brewer’s nonalcoholic beverages Malt Nutrine and Bevo. Then in 1915 and for 79 years, D’Arcy Advertising managed the Anheuser-Busch brand Budweiser as well as other Anheuser-Busch beverages. This ad for Bevo is from 1918 and features an “appetizing drink, wholly free from bacteria” for soldiers fighting in World War One. See if you can spot the D’Arcy logo. (St. Louis Media History Foundation archives)