Historic Personalities — Branch Rickey

When spring trees blossom in St. Louis, that can only mean one thing: baseball is back.

The Advertising Club enjoys a long and special relationship with our St. Louis professional sports teams. Over the decades, many in our sports community have also been members of the Ad Club and our Ad Clubbers have played major roles in promoting, broadcasting, and advertising our teams. From the earliest days of the Ad Club, it was understood that some of the city’s most effective advertising is for its professional sports. Successful teams instill civic pride, place St. Louis in a national spotlight, attract visitors to the city and add revenue to local businesses.

Today we highlight baseball innovator, Hall-of-Famer, and one-time former Ad Clubber Branch Rickey.

Branch Rickey is remembered for contributing to a positive shift in the color barrier in Major League Baseball with his signing of Brooklyn Dodgers infielder Jackie Robinson in 1947. But before Rickey helped take steps to integrate baseball, he was already an innovator and made his mark with the St. Louis Browns and Cardinals. Rickey started his professional baseball career as a catcher with the St. Louis Browns in 1905-1906, and the New York Highlanders in 1907 (renamed the Yankees in 1913) in a rather mediocre fashion. It was during Rickey’s time with the Highlanders that 13 consecutive Washington Senators stole bases on him in one game and by the end, Rickey had stopped bothering to throw. At the close of 1907, except for two brief appearances in 1914, Rickey’s professional playing days were over.

After a brief return to college coaching and law school, Rickey was offered a chance to join management of the St. Louis Browns in 1912 and eventually moved to coaching the team from 1913-1915. He went back to the front office in 1916. The Post-Dispatch on July 5, 1914 featured an article on “Dr. Branch Rickey, Professor of Baseball” that showcased his innovative baseball and coaching techniques like teaching baseball theory during spring training, developing batting cages, pitching machines and strike zone indicators, inventing sliding pits so players could safely learn how to slide into a base, and practicing the hit and run. The article opens by describing Rickey as,

“Collegian-Manager Gingers Up Tail-End St. Louis Browns With Peppery Injections From Philosophy of Socrates, Epictetus and Nietzsche – The ‘Will to Win’ and ‘Know Thyself’ Are Chief Stimulants in His Rejuvenating Dope – Efficiency Courses in Sliding, Base Running and Batting Mark New Departure in National Pastime.”

Rickey’s new approach did improve the last-place Browns, but only for a brief time. Soon with new Brown’s management, Rickey was gone. But, not for long. He found a new home across town when the St. Louis Cardinals hired him as president in 1917 and he helped the Cards to a third-place finish and their top record to date.

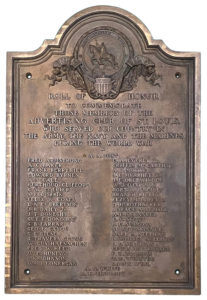

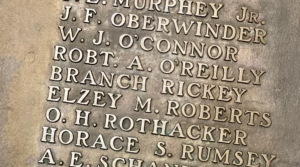

In 1918 and at 36 years old, Rickey joined the war effort in France during World War One as a major in the elite U.S. Army 1st Regiment Gas and Flame division. Other baseball notables he commanded in his unit included Ty Cobb and Christy Mathewson. Rickey’s service and Ad Club participation is immortalized in the bronze plaque that the Advertising Club of St. Louis commissioned to honor all Ad Club men who served in the World War (stay tuned for the rest of the story on this plaque in future posts).

When Branch Rickey returned from France, he found a financially strapped Cardinals team and took on the role of field manager in addition to president to save a salary. He managed the Cardinals until 1925 and moved back to the front office as vice president of the club. It was at this point that his skill as a baseball executive came into full force. He had already begun organizing today’s farm team system to develop home-grown players. He was a shrewd contract negotiator and observer of talent. He helped the Cardinals win the pennant and defeat the New York Yankees in 1926. In 1927, the Cardinals finished second, but a year later in 1928 and then in 1930 the Cards won the NL pennant, but lost the World Series each time. In 1930, Rickey signed Dizzy Dean and in 1931 the Cards defeated the Philadelphia Athletics to win the World Series. All the while Rickey was bringing up other home-grown talents like Pepper Martin, Ducky Medwick, and adding through trades like Leo “The Lip” Durocher. By 1934, the Gas House Gang was formed and the Cardinals won the World Series again.

Rickey resigned from the Cardinals organization in 1942, but not after signing Stan Musial in 1938 and winning the World Series in 1942. He went on to make more history with the Brooklyn Dodgers and Pittsburgh Pirates. In 1963, Rickey reunited with the Cardinals as a special consultant, witnessed another Cardinal World Series victory in 1964, and was fired in 1965.

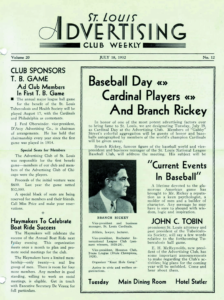

Ricky was a frequent guest speaker at Ad Club luncheons, and he paved the way for many future Cardinal baseball presentations at club luncheons over the years. In one of his last appearances with the Ad Club faithful in April 1964, Ad Clubbers gave the 82-year-old Rickey a standing ovation and awarded him the Order of the Brass Hat. According to the Post-Dispatch (April 29, 1964) Rickey saluted the Advertising Club of St. Louis for its long-time support of the ball club and he spoke warmly of baseball’s prominent role in integration (thanks in part to Mr. Rickey).

Branch Rickey gave his final speech in Columbia, Missouri on November 13, 1965 at the Daniel Boone Hotel. He was in Columbia for his induction to the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame. Days before the ceremony, an unexplainably high fever put Rickey into a St. Louis hospital for observation. With the doctors unable to determine the fever’s source, Rickey demanded to be released. No one wanted Rickey to attend the ceremony in Columbia, but he was insistent and arrived in Columbia in time to witness a cold and windy Missouri Tiger victory vs. Oklahoma. He later attended the Missouri Hall of Fame dinner and got up to give his speech. As he shared stories of moral courage and his long career, he suddenly stopped and said, “I don’t believe I’m going to be able to speak any longer.” He stepped back from the podium, collapsed, and fell into a coma. He never recovered, stayed in the Columbia hospital, and died on December 9, 1965 at 83-years-old.

Post-Dispatch sportswriter Bob Broeg wrote shortly after Rickey’s death,

“…to have experienced his last lucid moment on his feet, his voice vibrant and a capacity crowd of some 150 persons, open-mouthed, hanging on to his every word, ah, that’s the way Mr. Rickey would have wanted it – and that’s the way it happened.”

For many years, Ad Club members have worked on St. Louis Cardinals (and St. Louis Browns) marketing, advertising, broadcast production and promotional campaigns. Now it’s time to share your story. What do you recall about working with the Cardinals, Browns, or those areas related to sports marketing (beer, promotions, broadcasts)? What’s your favorite baseball memory? What’s your favorite baseball campaign or promotion? Share your stories and help us celebrate #AdClubSTL120.

- The Advertising Club of St. Louis Roll of Honor plaque commissioned to recognize Ad Club men who served in the U. S. military during World War I

- Close up of Ad Club member Branch Rickey on the Roll of Honor World War I plaque

- Branch Rickey was a frequent presenter at the Advertising Club luncheons. Here is the cover of the St. Louis Advertising Weekly from July 18, 1932 promoting baseball day at the Club.

- Branch Rickey and members of the St. Louis Cardinals Gashouse Gang June 13, 1933

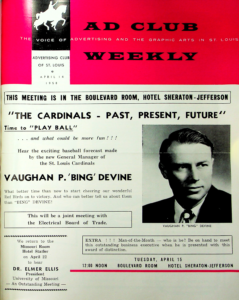

- The Advertising Club enjoys a long history celebrating baseball and the St. Louis Cardinals. New General Manager Bing Devine was guest of the Ad Club in April 1958 to talk Cardinals baseball. Devine, a St. Louis native and Ad Club member, served as Vice President and General Manager of the Cardinals from 1958-1964. Ironically, it’s often stated that Branch Rickey’s meddling into the Cardinals front office in 1964 contributed to Devine’s dismissal prior to the 1964 World Series as well as Rickey’s firing in 1965. Devine returned to the Cardinals from 1968-1978. Bing Devine is a member of the Missouri Sports Hall of Fame and is remembered for bringing Lou Brock to the Cardinals.

- Former Cardinals catcher and St. Louis native Joe Garagiola was guest of the club on July 14, 1959.

- Review of Joe Garagiola speech in the following Ad Club Weekly on July 20, 1959. Picture shows sports writer Bob Broeg and broadcasters Jack Buck and Harry Caray wearing catcher’s masks to “make Garagiola feel at home”

- Undated photograph from 1980s shows another Cardinals baseball day at the Ad Club luncheon. From L-R: broadcaster Jay Randolph, broadcaster Jack Buck, Ad Club officer Norm Stewart, broadcaster/former player Mike Shannon, coach Whitey Herzog.

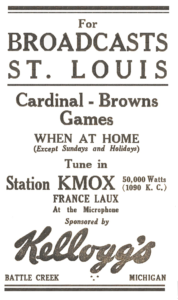

- 1935 KMOX advertisement for Cardinals and Browns radio broadcasts sponsored by Kellogg’s.

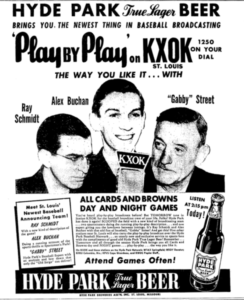

- Hyde Park Beer brings you St. Louis Cardinals and Browns baseball broadcasts on KXOK in this 1940 advertisement.

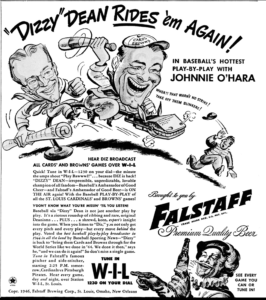

- Dizzy Dean and Falstaff Beer deliver Cardinals and Browns play-by-play on WIL Radio in this 1946 advertisement.

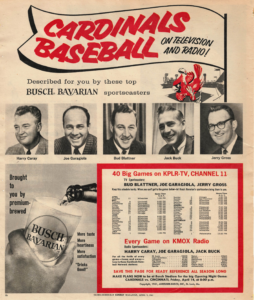

- Busch Bavarian Beer and KPLR-TV Channel 11 deliver televised Cardinals games and KMOX Radio deliver radio broadcasts in 1961.

For more archives, visit www.stlmediahistory.org